By Steve Austin Nwabueze

It has been a popular notion throughout the ages that fear of punishment can reduce or eliminate undesirable behavior. This notion has always been popular among criminal justice thinkers. These ideas have been formalized in several different ways. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham is credited with articulating the three elements that must be present if deterrence is to work: The punishment must be administered with celerity, certainty, and appropriate severity. These elements are applied under a type rational choice theory.

Rational choice theory is the simple idea that people think about committing a crime before they do it. If the rewards of the crime outweigh the punishment, then they do the prohibited act. If the punishment is seen as outweighing the rewards, then they do not do it. Sometimes criminologists borrow the phrase “cost-benefit analysis” from economists to describe this sort of decision-making process.

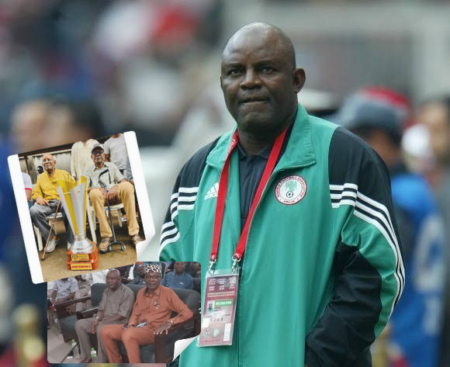

The world woke up on Friday, August 16, 2019 to learn that a life ban has been imposed on ex Super Eagles and Olympic Eagles coach, Samson Siasia. This development has sent legal shock waves across the continent and especially amongst soccer lovers. In a statement released by the world football governing body at about 18:00 hours Nigerian time, FIFA stated as follows:

“The formal ethics proceedings against Mr. Siasia were initiated on February 11, 2019 and stemmed from an extensive investigation into matches that Mr. Wilson Raj Perumal attempted to manipulate for betting purposes.

“This large-scale investigation was conducted by FIFA via its competent departments and in cooperation with the relevant stakeholders and authorities. In its decision, the adjudicatory chamber found that Mr. Siasia had breached art. 11 (Bribery) of the 2009 edition of the FIFA Code of Ethics and banned him for life from all football-related activities (administrative, sports or any other) at both national and international level. In addition, a fine in the amount of CHF 50,000 has been imposed on Mr Siasia.

“The decision was notified to Mr. Siasia today, the date on which the ban comes into force.”

The former player and coach has since denied any wrongdoing in the saga and has vowed to clear his name; stating that his lawyers are reviewing the ruling with a view to taking a firm decision on the mater. In addition, the Nigeria Football Federation, NFF, has thrown its weight behind the embattled former coach.

The NFF in an August 19, 2019 statement said that its lawyers were reviewing the decision by the FIFA Ethics Committee. The NFF’s Acting President, Seyi Akinwunmi, said on Monday that the Federation had already reached out to the former U20, U23 and Super Eagles head coach and is aware that he is receiving appropriate legal advice.

“The NFF was shocked to learn of the investigation and subsequent decision by the FIFA Ethics Committee (Adjudicatory Chamber) placing a life ban on Mr. Samson Siasia. But we have however now received documents, including one known as the Motivated Decision, and we have handed them to our lawyers to study and provide legal advice to the Federation. It is a massive sanction on one of our legends. Siasia is a football legend but most importantly he is a Nigerian. We must therefore be interested in the matter and be properly advised.”

As expected, a lot of reactions has trailed the FIFA ethics committee decision. Whilst a lot of people have come out to condemn what many have termed “unwholesome practice”, others have questioned why the proceedings were kept under wraps until a few months later. By the statement, it appears that investigations into the saga had been on-going since February 2019.

This writer hastens to point out that he is not in possession of the documents forming the background of the decision and would refrain as much as possible from commenting on the factual issues which he is not privy to. Suffice to say that this article would be firmly riveted on an analysis of the FIFA Disciplinary code.

By the facts made available to the public, which it must be stated are quite sketchy at the moment, the alleged offence was committed in 2009 even though the exact timeline of the alleged infraction is unknown. By FIFA’s statement, Siasia breached Article 11 of the FIFA Code of Ethics 2009 revolving around bribery of an official. It is pertinent to reproduce the provisions of Article 11. The provision states as follows:

1. “Officials may not accept bribes; in other words, any gifts or other advantages that are offered, promised or sent to them to incite breach of duty or dishonest conduct for the benefit of a third party shall be refused.

2. Officials are forbidden from bribing third parties or from urging or inciting others to do so in order to gain an advantage for themselves or third parties”.

It is important to remember that the alleged offence of Siasia was that he was allegedly found “guilty of having accepted that he would receive bribes in relation to the manipulation of matches in violation of the FIFA Code of Ethics” (FCE). It is not the case of FIFA that he was actually found guilty of receiving bribes. Whilst the sketchy factual background did not reveal that Siasia actually collected a specific amount from the offeror, his offence appears to be grounded in his tacit “acceptance” of the offered gratification without actually consummating the offence with an outward act of collecting a bribe. This conjecture is discernible from the terse statement from FIFA indicting Siasia which fails to mention the amount offered and the amount accepted by the culprit. However, it appears that the Ethics Committee had applied the deterrence theory of punishment in its bid to ensure that the hard-line stance of the football governing body is not compromised. This conclusion can be gleaned from an excerpt of the final award by the Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS) in the case of Amos Adamu v FIFA where the panel held as follows:

“Match-fixing, money-laundering, kickbacks, extortion, bribery and the like are a growing concern in many major sports. The conduct of economic and business affairs related to sporting events requires the observance of certain “rules of the game” for the related activities to proceed in an orderly fashion. The very essence of sport is that competition is fair. This is also true for the organization of an event of the importance of the FIFA World Cup, where dishonesty should have no place. In the Panel’s view, it is therefore essential for sporting regulators to demonstrate no tolerance against all kinds of corruption and to impose sanctions sufficient to serve as an effective deterrent to people who might otherwise be tempted, because of their greed, to consider adopting improper conducts for their personal or political gain. Members of the FIFA Executive Committee are an obvious target for those who wish to influence the designation of the country appointed to host the FIFA the World Cup”.

Sometime in January 2018, a Ghanaian referee, Joseph Lamptey was banned from all football related activities by the world football governing body for being complicit in the manipulation of a world cup qualifying match between Senegal and South Africa on November 16, 2016. The CAS in determining the appeal underlined FIFA’s commitment to protecting the integrity of football and its zero-tolerance policy on match manipulation. It is difficult to understand the underlying jurisprudence of the present ban in view of the existing precedents on the matter, none of which appears to support the “accepting to receive bribe” principle being laid down in the present case.

Perhaps we can take a look at the Amos Adamu case and what it establishes to see whether there is precedent for this decision. It is conceded that the facts of the two cases are not markedly different from each other. A brief rehash of the factual background in the Amos Adamu case is necessary.

The Undercover Journalists’ Investigations

On 17 October 2010, the British weekly newspaper, Sunday Times published an article entitled “Foul play threatens England’s Cup bid; Nations spend vast amounts in an attempt to be named World Cup host but as insight finds, $ 800,000 offered to a FIFA official can be far more effective”. The newspaper reported strong suspicions of corruption within FIFA in connection with the selection process to host the FIFA World Cups. The article suggested that corruption was widespread within FIFA and came to the conclusion that, in the current state of affairs, it was more effective and less costly to obtain the organization of the World Cup by offering bribes rather than by preparing and filing a thorough and well-documented bid. As a final point, the article concluded as follows:

“Football has enough trouble maintaining fair play on the field. FIFA has to ensure that there is fair play off it, too, by stamping out corruption and cleaning up the World Cup bidding process. FIFA badly needs to introduce more transparency into the process and keep its decision makers under tighter control. That means an end to payments into private bank accounts or pet projects. It means each committee member judging the merits of the bids, not the bribes on offer. The Olympics has cleaned up its act after a series of bribery scandals, culminating in Salt Lake City in 2002. We have a right to expect no less of the World Cup”.

The covert inquiry had been conducted by some Sunday Times journalists who had approached several FIFA executives and former executives pretending to be lobbyists working for a private company allegedly named Franklin Jones, hired by a group of American companies eager to secure deals in order to unofficially support the official bids presented by the United States Soccer Federation for the 2018 and the 2022 FIFA World Cups.

With specific regard to Dr Adamu, during the Summer of 2010, he was contacted via email and telephone by two reporters – a man and a woman – who did not reveal their true identities and profession but presented themselves as “David Brewster” and “Claire” of Franklin Jones. The reporters obtained to organize two meetings with Dr Adamu, one in London and one in Cairo, in August and September 2010 respectively. On August 31, 2010, in a London hotel bar, the Appellant met the two undercover reporters allegedly working for Franklin Jones. The conversation lasted about 45 minutes and was video and audio recorded by the two reporters, without the knowledge of Dr Adamu. On September 15, 2010, in the garden bar of a hotel in Cairo, Dr Adamu had another meeting with the same two undercover journalists. The conversation lasted about 30 minutes and was also recorded on video and audio tape, without the knowledge of Dr Adamu. These two meetings culminated in an agreement between the parties to the effect that Dr Adamu would be trading his vote for cash in support of the United States bid. Expectedly, the sting operation came to light and Dr. Adamu was duly banned by the FIFA Ethics Committee. His subsequent appeals to the Appeals committee and the CAS were unsuccessful.

Amos Adamu v FIFA – The Appeal

Following the decision of the FIFA Appeal Committee upholding the decision of the ethics committee, Dr Adamu, a member of the FIFA Executive Committee (hereinafter also the “Appellant”) – against a decision of the FIFA Appeal Committee, which held him responsible for breaching various provisions of the FIFA Code of Ethics (articles 3, 9 and 11). The FIFA Appeal Committee imposed on him a ban from taking part in any football-related activity at national and international level for a period of three years as from 20 October 2010 as well as a fine of CHF 10,000. The specificity of the case lies in the fact that the Appellant was filmed and recorded by hidden cameras and recorders, while meeting twice with undercover Sunday Times journalists posing as lobbyists purporting to support the United States football federation’s bid for the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups. The video and audio recordings of those meetings (hereinafter “the Recordings”), passed on by the Sunday Times to FIFA, are the basis of FIFA’s case against Dr Amos Adamu.

Proceedings before the appeal committee

On February 3, 2011, the FIFA Appeal Committee heard the Appellant. On April 12, 2011, the Appellant was notified of the reasoned decision issued by the FIFA Appeal Committee (hereinafter the “Appealed Decision”). The FIFA Appeal Committee, inter alia, held as follows: 1) the proceedings before the FIFA Ethics Committee were properly carried out; 2) the FIFA Ethics Committee correctly applied the law in including the football-related activity on a international and on a national level in the ban imposed upon the Appellant; 3) the evidence consisting of written transcripts and recorded materials such as the audio and video tapes were admissible; and 4) the Appellant’s right to be heard was not infringed. The FIFA Appeal Committee found that there was sufficient evidence to establish that the Appellant accepted unjustified advantage against his vote in favour of the American bid and that the requirements of Article 11 para. 1 FCE (Bribery) were met. In any event, it considered that the Appellant’s behaviour was too ambiguous with regards to the specific standard of conduct requested by the said provision. The FIFA Ethics Committee deemed that the Appellant violated the principles set in article 9 FCE (Loyalty and Confidentiality) as well as the duty of disclosure of illicit approaches prescribed by the applicable regulations in failing immediately to report to FIFA that he had been in receipt of orders.

On June 20, 2011, FIFA submitted an answer and respectfully requests the CAS to issue an award 1) rejecting Dr. Adamu’s prayers for relief; 2) confirming the Appealed Decision; and 3) ordering Dr. Adamu to pay in full or pay a contribution of no less than CHF 40,000 towards the legal fees and other expensed incurred by FIFA in connection with these proceedings.

In its decision, the CAS three-man arbitral panel led by Prof Massimo Coccia held that there was no mitigating factor in the appellant’s case. Indeed, the appellant did express regrets for the bad publicity and damage caused to FIFA’s image by the coverage of his meeting with the journalists. At the same time, he has constantly denied any wrongdoing, let alone the violation of any provision of the FCE. The Appellant submits that given his clean record and the fact that he was not the instigator of the bribery, the sanction imposed is by far too severe. The Panel accepts that, until the recent events under scrutiny in this appeal, the Appellant’s reputation was untarnished. Accordingly, the Panel found that, pursuant to Articles 22 and 10.c FDC in connection with Article 17, a ban from taking part in any football-related activity at national and international level (administrative, sports or any other) for a period of three years as from October 20, 2010 as well as a fine of CHF 10,000 is not a disproportionate sanction and might even be deemed a relatively mild sanction given the seriousness of the offence. Therefore, the Panel held that the Appealed Decision must be upheld in its entirety, without any modification. In sum, the Court of Arbitration for Sports held as follows:

1. The appeal filed by Dr Amos Adamu against the decision issued by the FIFA Appeal Committee on 3 February 2011 is dismissed;

2. The decision issued by the FIFA Appeal Committee on 3 February 2011 is confirmed;

3. Dr Amos Adamu shall pay the amount of CHF 10,000 (ten thousand Swiss Francs) to FIFA as contribution towards its costs; and

4. All other motions or prayers for relief are dismissed.

A comparison between Siasia’s and Adamu’s cases

Thus, what is discernible from the factual background of both cases is at best, an attempt by both men to compromise the integrity of football as there was no evidence of an actual receipt of financial gratification by both men. Indeed, both men were charged under Article 11 which with the greatest respect, contains no reference to attempts. This is unlike Article 18 of the 2019 FIFA Code of Ethics which is the equivalent of Article 11 of the 2009 FIFA Code of Ethics. In drawing this distinction, it is important to cite the relevant provisions of Article18 of the 2019 FCE which provides as follows:

“Anyone who directly or indirectly, by an act or an omission, unlawfully influences or manipulates the course, result or any other aspect of a match and/or competition or conspires or attempts to do so by any means shall be sanctioned with a minimum five-year ban on taking part in any football-related activity as well as a fine of at least CHF 100,000. In serious cases, a longer ban period, including a potential lifetime ban on taking part in any football-related activity, shall be imposed.”

By the ipssisima verba of this provision, a conspiracy or an attempt to influence the outcome of a match would be punishable by the disciplinary body. This provision clearly “covers’ the field in respect of what the CAS decided in the Adamu case and what the Ethics Committee decided in the Siasia case. The old code (2009) under which both men were charged contain no such provisions. While conceding that the damning video and audio evidence submitted by FIFA might have tilted the case against him slightly, the writer struggles to understand the jurisprudential basis of the Ethics Committee’s decision. As the football world awaits further details of this decision, certain posers agitate informed minds as we strive to unravel this legal mystery to wit:

i) Was the Ethics Committee trying to make a statement with its decision to serve as a deterrence to would-be offenders?

ii) What quantum of evidence was made available to the Ethics Committee?

iii) Did the Committee misapply the provisions of art.11 in its evaluation of evidence even without an actual receipt of gratification?

iv) Given the timing of the proceedings, did the Committee unwittingly, apply the wrong Code in arriving at its decision?

As we labour to get answers to these posers, it is clear that the Committee wanted to make a statement with its decision given the rampant cases of match fixing in football. What is however not clear is how it arrived at its conclusion. As for the quantum of the evidence available to it, the statement alluded to its “extensive investigation”. What is available to the mainstream media is the statement credited to Mr. Wilson Raj Perumal, the Singaporean dubbed “the world’s most notorious match-fixer” indicting Mr. Siasia. It is unclear whether there is a corroborative evidence of his statement and the extent to which this corroborative evidence established his claims.

On the (mis)application of Article 11 of the 2009 edition of the FCE, a literal interpretation of the provisions shows that attempt and or conspiracy to receive gratification are not covered by the provisions. This lacuna as highlighted above, has been addressed in the 2019 edition with a broader definition of the misconduct envisaged under the Code. If these offences have not been captured, on what basis then did the Committee arrive at its decision in this regard? if we can rationalize the decision on the basis of the earlier decision of the CAS in Adamu v FIFA, how come the Committee imposed the maximum punishment of a life-ban on Siasia and not the temporal one imposed by the CAS? It is important to remember that the CAS was very scathing in its remarks in condemning the actions of Dr. Adamu who at the material point in time was an Executive Member of FIFA. Siasia as at March, 2009 was the coach of the Flying Eagles of Nigeria. It is therefore surprising that whilst an Executive member of FIFA received what could be described a “slap on the wrist”, the Ethics Committee decided to go the opposite way with Siasia. Such seeming inconsistencies in decisions can be avoided if a fact-intensive analysis is undertaken by the Committee before releasing its decision. Had the Committee embarked on this arduous but important task, it would have discovered the factual divergencies in both cases. The decision is also not on all fours with the Lamptey decision since Article 11 was not considered. Lamptey was charged with breach of Article 69(1) i.e. unlawfully influencing match results. In sum, the writer holds the humble view that art.11 has been misapplied by the Ethics Committee.

The FIFA code of Ethics for 2019 was released sometime in June 2019 with far reaching amendments to the 2017 edition. By the sketchy facts made available to the football loving public, the proceedings commenced in February 2019 and ended on or before August 16 2019. This seeming coincidence pales into insignificance when Article 18 is read in the context of the decision particularly the strong language used by the draftsman. At first blush, it would appear as if Article 18 was considered. There are however, two reasons why this is impossible. In the first place, by the principle of retroactivity, Siasia cannot be charged under a law that was non-existent as at the time the alleged offence was committed. Secondly, by Article 10(c) of the FCE, offences relating to match-fixing can only be prosecuted not later than five years after they were committed. The alleged offence here was however, allegedly committed in 2009. Interestingly though, there appears to be a willingness by the Committee to use this as a test case for setting an example to would-be offenders, if this is the intention, the jurisprudential basis appears rather blurred. For the moment, we can only wait patiently for the decision of the FIFA Appeals Committee and the Court of Arbitration for sports should Siasia decide to initiate an appeal as expected.

Disclaimer: The present article reflects only some personal views and general remarks drawn from a legal analysis of the decision of the FIFA Ethics Committee and why same should be set aside on appeal. The author confirms he has no professional involvement in this particular matter, whether past or present.

Steve Austin Nwabueze is a lawyer and team lead of the dispute resolution and sports law department of Perchstone & Graeys LP, Lagos Nigeria.

1 Comment

ONE REASON I WANT TO REMAIN A LAWYER. TRUTH IS BARE, WHITE AND BLACK